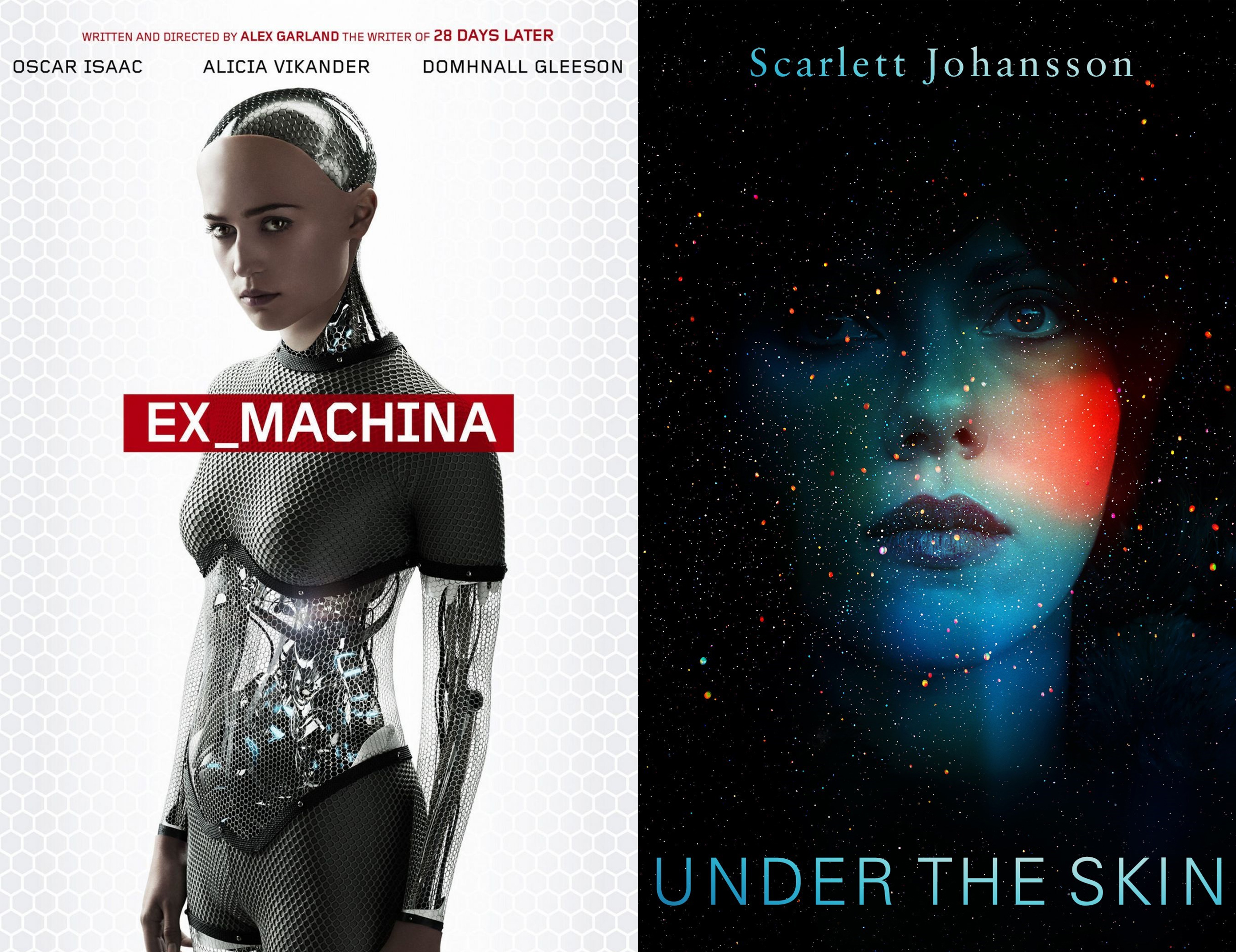

Two of my favorite science fiction films of the past decade are also brilliant depictions of gender dynamics. It’s impossible to discuss without including spoilers, so I’m going to assume here that you’ve already seen them, and tell you why it’s worth watching them together.

Ex Machina (2014) is an exploration of artificial intelligence, but it is also a fable of what happens when men underestimate women. Nathan (Oscar Isaac) is a terrifyingly charismatic tech-bro genius whose robot creations reflect the dominant trend in real-life robot development: female-bodied, sexualized, servile.

Nathan’s misogyny is overt and violent. He’s the Bluebeard of the story: a sadistic prison guard whose aggressive machismo characterizes every interaction he has. He’s invited his meek, shy employee, Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) to be the very first test audience for Ava, Nathan’s latest AI creation (Alicia Vikander). Nathan is charming and cool, but there’s an intense, alpha male menace beneath every action. Caleb expresses his awe at Ava’s intelligence, but wonders why she’s been made female, and beautiful.

Caleb: Why did you give her sexuality? An AI doesn’t need a gender. She could have been a grey box.

Nathan: Actually, I don’t think that’s true. Can you give an example of consciousness at any level, human or animal, that exists without a sexual dimension?

Caleb: They have sexuality as an evolutionary reproductive need.

Nathan: What imperative does a grey box have to interact with another grey box? Can consciousness exist without interaction? Anyway, sexuality is fun, man. If you’re gonna exist, why not enjoy it? You want to remove the chance of her falling in love and fucking? And the answer to your real question, you bet she can fuck.

Caleb: What?

Nathan: In between her legs, there’s an opening, with a concentration of sensors. You engage them in the right way, creates a pleasure response. So if you wanted to screw her, mechanically speaking, you could. And she’d enjoy it.

Caleb: That wasn’t my real question.

Caleb is visibly off-put by Nathan’s cavalier objectification (even if these androids are, technically speaking, objects), and Nathan’s frank vulgarity is also meant to intimidate Caleb, who he clearly sees as weak.

Even this “disco non-sequitur”, an absurd comedic break from the increasing horror of the film, is about Nathan displaying his sexual and physical dominance over women and, by extension, over Caleb. [And I cannot talk about this movie without sharing this clip; it’s everything I love about this film in one scene]

Caleb, as sweet as he seems, holds his own sexist assumptions. From his first test conversations with Ava, he’s immediately drawn to her charm and beauty. As their relationship progresses, he’s convinced of her autonomy and her desire for freedom, and believes he’s the one who must help her gain it. Unfortunately, his perception of female autonomy is limited by his own inexperience and social conditioning. His view of women is infantilizing; he’s flattered to be needed, to be her potential savior, and he sees Ava as his grateful conquest. However, Ava is far more aware than Caleb realizes; she has been manipulating his male ego by posing as more vulnerable than she really is.

By objectifying his creations, Nathan has underestimated their intelligence. By romanticizing them, Caleb underestimated their will. Each man manifests a type of sexism, and for each, it is their undoing.

* * *

Under the Skin (2013) stars Scarlett Johansson as a mysterious alien who strongly resembles Scarlett Johansson in a dark wig, roaming the streets of Glasgow in a cargo van, picking up strange men, and luring them to their doom. She is the embodiment of weaponized femininity, her wiles and her red lipstick proving irresistible to every target.

Behind-the-scenes stories of filming are rarely more than interesting trivia, but in the case of Under the Skin, knowing how it was filmed is almost essential. Johansson actually drove this van around Glasgow for hours, in character, attempting to pick up strange men. Hidden cameras captured these encounters; if the scene went well, crew had the men sign a waiver after the fact. There were a few scary, unplanned moments; at one point the van is surrounded by hooligans banging on the windows and shouting at her. In order to play a predator of men, Johansson put herself into a relatively vulnerable position. By filming this as documentary, though, the film demonstrates easily how little suspicion a man brings to this scenario. It’s impossible to imagine woman after woman so readily getting into an unmarked van with a strange man, even if he strongly resembled Tom Hardy in a bad wig.

This (briefly NSFW) clip is of the first successful capture we see. The alien’s flirtatiousness is sweet and natural, a sharp contrast of what we see of her when she’s alone- eyes dead, mouth grimly closed. Their rapport feels genuine. Because men aren’t socialized to be suspicious of sexual attention, they fall easily into her trap.

She asks the man if he has a girlfriend, which could just be flirting, but she asks other potential victims, too, about whether they have family or friends. She only pursues men who are alone, vulnerable, who won’t have people asking after them. Any woman who’s lied about having a boyfriend or husband to evade male attention would recognize this tack immediately. Male obliviousness to this dynamic is their doom.

This film isn’t just a black widow gender-revenge story, however. As the alien spends more time among humans, her blank indifference shifts into curiosity, even something approaching empathy. After an encounter with a cautious, sympathetic young man with a physical deformity, she catches a glimpse of herself in the mirror and is momentarily mesmerized by her own human face. She frees the young man and then runs off herself, directionless, into the Scottish countryside.

She meets a quiet, gentle man who seems content to simply be near her and protect her. She barely speaks, unable to convey the confusion and change she’s experiencing- a burgeoning of feeling, impulses towards a sensitivity that is human, feminine. Their unspoken intimacy deepens, but during an attempt at consummating their feelings, the alien discovers her human appearance is only skin-deep. She has no anatomical ability to have intercourse. Her spiraling identity crisis sends her on the run, again, wandering directionless through the woods.

The alien’s burgeoning sense of affinity with humans has piqued a kind of compassion, which we like to think of as a defining characteristic of humanity. Unfortunately, not all humans are humane. Her newfound vulnerability has left her without any defenses against man’s worst impulses, and she’s targeted by a creepy, aggressive logger who ultimately destroys her.

It’s a nuanced look at societal gender norms; the film is quite sympathetic to the majority of men in the film, while also clearly demonstrating how one-sided the power dynamic often is.

* * *

Ex Machina gleams with a Kubrickian, Silicon Valley sleekness, while Under the Skin alternates between gloomy Scottish realism and stark, abstract spaces. The dialogue in Ex Machina is sparkling, crisp, while Under The Skin is nearly free of conversation but for short exchanges between the alien and her potential victims, its soundscape shaped by eerie strings and echoing, metallic percussion.

Interestingly, each film features a scene where the male filmmakers attempt to disarm the male gaze- both Ava and the alien have moments alone in front of a full-length mirror, nude, where they reflect on their apparent female-ness, grappling with the power and vulnerabilities of their form. Neither film has any actually human women. In both cases, the women are further Othered, as an android or an alien, in a way that both exaggerates difference and asks the audience to consider what actually is human, or female.

In Ex Machina, Ava uses her understanding of male ego to manipulate her way into power and freedom, overcoming her lack of brute physical strength. The alien of Under the Skin uses femininity as a tool of manipulation as well, but she herself is under the control of her male-bodied handler, and is ultimately victimized by a human man. She seems powerful, but it’s an ill-gotten power, spoils of the patriarchal bargain. Both films highlight the narrow, dangerous path that women are forced to walk in order to survive in a society which is invested in keeping them subordinate.